Ball & Chain bar and lounge and the building it occupies offers a history as colorful and as fascinating as any structure on this portion of Calle Ocho, an area increasingly considered to be the center of Little Havana.

Historic Ball & Chain Miami 1939 Tax Card

But before there was a Calle Ocho, and even a Tamiami Trail, the mid-1900s name for Southwest Eighth Street, there was a dirt road, over which carriages and motor vehicles brought produce to downtown Miami for sale and shipment. The Trail, as it was commonly known, was also important because it represented the southern terminus of a national road, Highway 41, which began in the Midwest. In the era preceding superhighways, Highway 41 was a major entry route, via the Everglades, into Miami. Eventually, Southwest Eighth Street was paved and lined with commercial businesses, a movie theater, churches, and eateries in a neighborhood offering an intriguing demographic mix: a growing Jewish population standing side by side with a Deep South constituency.

Ball & Chain Saloon opened in 1935. The business remained there through the end of the 1950s, although its name changed slightly from time to time. In 1949, for example, it was Himmel’s Ball & Chain; in 1953, it was called the Ball & Chain Tavern.

The fortunes of Ball & Chain changed significantly in the 1950s, following its purchase by Ray Miller, Henry Schechtman, and others. Ray Miller was a felon and a Teamsters Union, Local 320, organizer and Henry Schechtman was a Jewish entrepreneur who often operated outside of the law. In a period of less than two months in the fall of 1957, Schechtman was arrested for burglary and for “attempting to pry open the deck lid of a jewelry salesman’s car.” Schechtman bought additional nearby properties, including the Tower Hotel, a former hospital dating to the early 1920s. Miller’s problems with the law included an arrest for public drunkenness, which he branded a “grudge charge” and attributed it to a disgruntled employee of a neighboring business.

According to his two sons, Schechtman dealt in stolen liquor and bootleg cigarettes, was part of a Jewish mob and served prison time. It would seem Ball & Chain was an appropriate name for his club. Schechtman was an imaginative businessman who staged bare knuckle fights behind the Tower Apartments. The times along Southwest Eighth Street were changing in that expansive post World War II era as more businesses filled the thoroughfare. With its rounded contours and RKO tower, the Tower Theater, standing across the street from Ball & Chain, was a popular draw for moviegoers. Used car dealers, other restaurants, an ice cream parlor, hardware store, gasoline stations, and even a hobby shop stood nearby Ball & Chain bar and lounge.

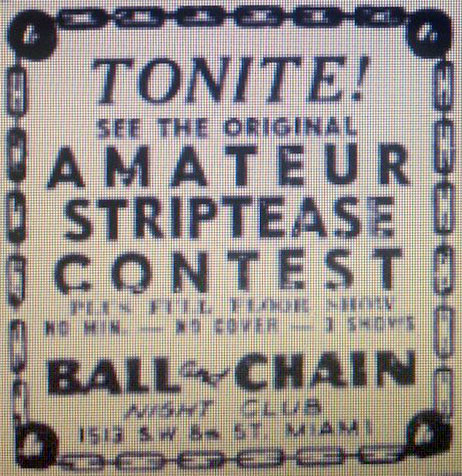

Ball & Chain featured entertainers who performed in the commodious venue with its stage in center, a long bar off to the west side of the room, tables sprinkled throughout the venue, and an alternative entranceway on the east side of the building for those quick getaways. A haunting painting of a prisoner in traditional garb and tethered to a ball and chain announced that entry point. Today that wall represents the western edge of the wildly popular Azucar ice cream parlor.

Ball & Chain Miami

Ball & Chain had more than one owner during its first twenty-five year run, and it achieved some notoriety during this time. Gambling was rampant in the 1930s and throughout the 1940s in Miami. And the era was also notable for the closing by local law authorities of nightspots for reasons of gambling and liquor law violations. Even the Ku Klux Klan, by then a diminished force in Miami, but still viewing itself as a morals’ arbiter, was responsible for trashing the notorious La Paloma Club in northwest Miami, because it viewed the nightspot as a den of iniquity. Bars and nightclubs farther west on Southwest Eighth Street were shut down by law authorities, as well.

Interestingly, D. C. Coleman, the Dade County sheriff throughout that era, lived just two blocks from Ball & Chain. Gambling was also a part of the offerings of Ball & Chain in the late 1930s-early 1940s, as noted in a scathing reference in the Miami Herald, c. 1941, which took the club to task for “brazenly” dismissing a guard who had stood at the door of the club and who was expected to warn employees inside that a police raid was coming. For the Herald, the elimination of this security figure meant that the Ball & Chain was now confident that there would be no gambling raids by the police.

Although it is not known when the Ball & Chain began to feature black entertainers, African Americans were already making their mark by the late 1940s early 1950s on Miami Beach and in nightclubs along Biscayne Boulevard. The Clover Club on the Boulevard, along with the Copa City club on Miami Beach’s Belle Isle offered entertainment by the Ink Spots and Josephine Baker, among others. The flamboyant singer and dancer who had wowed audiences in Paris in the 1920s, and, subsequently, many parts of the U.S., Baker insisted in her contract with Copa City that she would only perform before biracial audiences. Baker and her representatives recognized here the deeply segregated nature of Greater Miami, which differed little from other Deep South cities in terms of race.

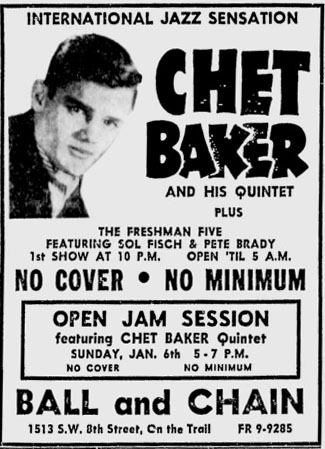

Schechtman’s sons insisted that Lena Horne, Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole and Louie Armstrong were among the stellar black performers who appeared at Ball & Chain, but prolonged research into their assertions has turned up only Billie Holiday, Count Basie, and Chet Baker, a talented white musician, as entertainers who appeared on a somewhat consistent basis in the final half of the 1950s. Billie Holiday was a welcomed figure in the Schechtman household in the Tower Apartments, even babysitting for the family. On one occasion, after the 5 o’clock a.m. closing, Mr. Schechtman returned to the family quarters only to find the great black singer with a needle in her arm. Billie died a few years later. She had had a long standing heroin addiction.

Chet Baker @ Ball & Chain

Many black entertainers appearing in the Greater Miami area would retreat to clubs on the Miami mainland after performing downtown and would often jam before an enraptured audience, including those at Ball & Chain. The “Count” also performed before enthusiastic daytime audiences on weekends in what were billed as jam sessions. (One of the alluring features of Ball & Chain bar and lounge for black musicians was the understanding that they could reside after their appearances at the Tower Apartments.)

At jam sessions, members of the audience were invited to come up to the stage and “strut their stuff” musically while often accompanied by the great musician. Not everything was euphoric with the “Count” and the ownership of Ball & Chain, however. In January 1957, Count Basie was paid by Ball & Chain $5,100.00, which was what it grossed from his multi-day stint there. Yet Basie’s contract called for a payment of $13,000. The Count sued for the balance owed and won a judgement of $5,000 effectively putting the club out of business. In 1958, the Copa Lounge Tavern was occupying the space that for more than twenty-two years was Ball & Chain.

The Copa, as some called it, was a distant cry from Ball & Chain bar and lounge, for it lacked the color and live entertainment of its predecessor. Yet, those who worked at the Copa were aware of Ball & Chain bar and lounge and the caliber of its entertainment, often telling bar patrons that Nat King Cole or other black entertainers performed there.

By the end of the 1950s, a large influx of Cubans, fleeing, first, the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, and, later, that of Fidel Castro, poured into a neighborhood, which was also experiencing a flight of long time residents to the new suburbs west of it. By 1967, the strong Cuban presence in the neighborhood, as well as among the businesses on Southwest Eighth Street, prompted many to refer to the area as Little Havana and to its main artery as Calle Ocho (as early as 1960, the Tower Theater was offering Spanish subtitles to first run American movies in recognition of the changing demographics).

In the same year, 1967, the Copa yielded to a new business in the space at 1513 Southwest Eighth Street: the Futurama furniture store. Futurama operated from this address till the mid-1990s, after which the venerable building stood vacant. In the first decade of the new century, the Barlington Group, already heavily invested in Little Havana real estate and with a growing reputation as a firm guided by a determination to bring significant improvements to Little Havana, began an extensive renovation of the building in preparation for its reopening as Ball & Chain. Once again food, drinks, and the liveliest entertainment, under the storied history of a long ago moniker, are on offer to guests from near and afar in a neighborhood now experiencing gentrification and a tourist boom unlike anything that has come before. Ball & Chain is again one of the premiere bar and lounge Miami Florida has on offer.